Learning from Indonesia: Local Wisdom for Sustainable and Inclusive Land Use

Indonesia’s growing population and exposure to severe climate events has focussed national attention on the need to ensure its future food security and sufficiency.

Since 2020, the country has vastly expanded its Food Estates Programme with the aim of converting four million hectares of land for food production by 2029. For such a large and varied country, home to megadiverse ecosystems and a complex patchwork of local agricultural practices, this programme will inevitably involve trade-offs.

In this blog, Cosmo Rana-Iozzi, Senior Project Officer for LEAF Indonesia at the University of Sussex, shares insights from the project’s work on land-use interventions that enhance food security, biodiversity, climate resilience, and livelihoods, while remaining rooted in local knowledge and realities.

Sustainable and Inclusive Land-Use Rooted in Local Wisdom

From longstanding indigenous traditions of communal forest farming to more recent initiatives in multifunctional land use, communities across rural Indonesia balance a range of ecological and socioeconomic needs. National initiatives to increase food production can and should engage with these local contexts.

In villages across Gorontalo, East Kalimantan and West Papua provinces, distinct and longstanding systems of forest farming and traditional rules are still practiced. These systems exist alongside and interact with varied and shifting climate and market contexts. Local knowledge of the land offers valuable insights into how integrated, multifunctional land use might balance food security with ecosystem conservation and socioeconomic need.

Harvests of tree products have long been integrated with that of annual crops to ensure the sustainability of the food supply in rural Indonesian villages. In Gorontalo the Ilengi system of land management ensures that traditional leaders of local, and otherwise marginalised, communities continue to have a say on the planning and planting of sites.

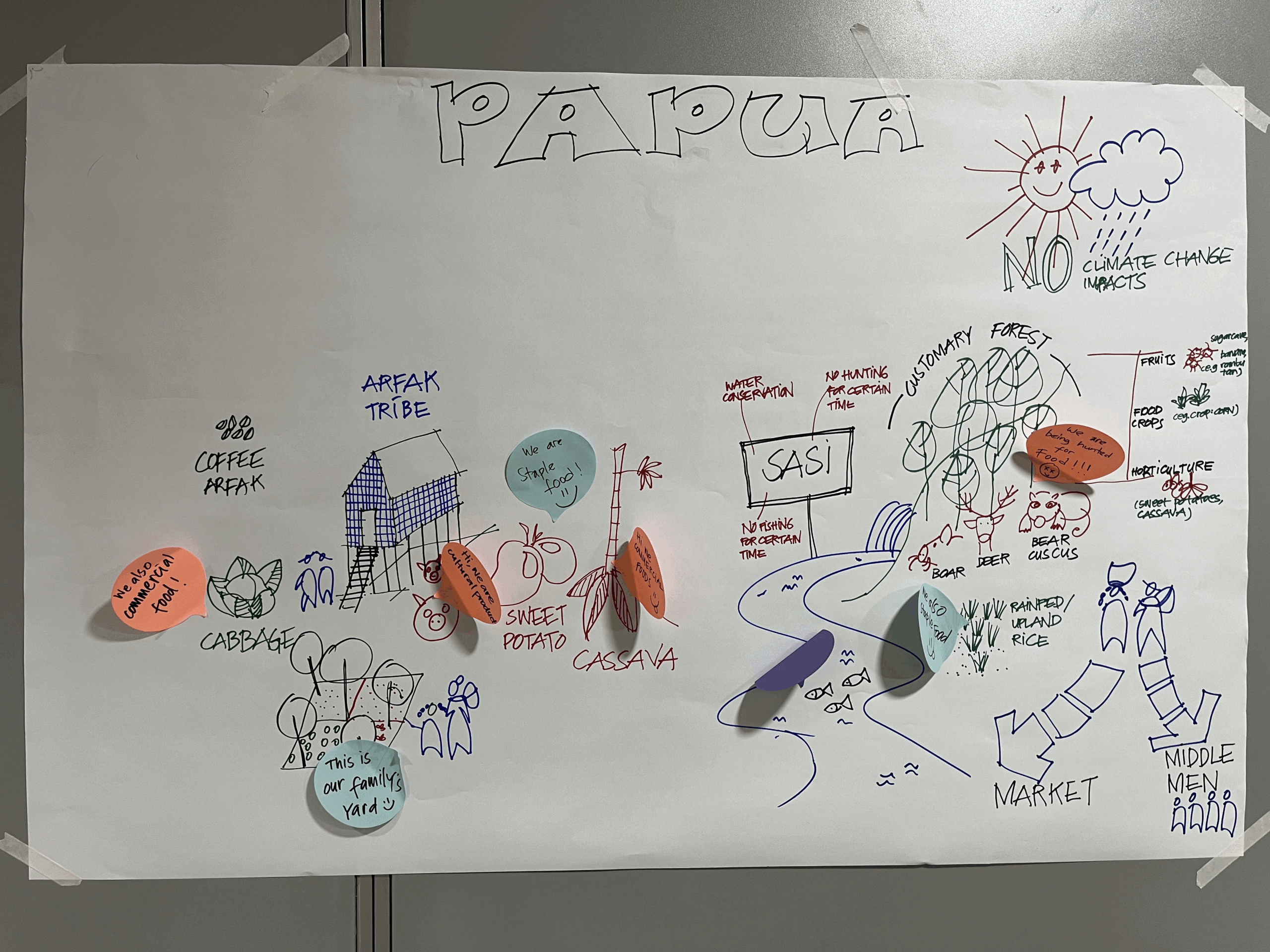

In Papua, Sasi still lays down customary law underpinning traditional signs and markings keeping certain forest areas and products off-limits. Both agroforestry systems ultimately manage a landscape resembling a natural forest, but one geared to sustainably contribute to local food security and incomes.

Indonesia’s dipterocarp forests, home to some of the country’s most biodiverse and resource-rich ecosystems, are largest in Kalimantan, but recent changes in cultivation have threatened their survival. This has also impacted the traditional local Dayak system of gardening, Lembo. Grown outside households, by roadsides and in the forests themselves, Lembo gardens are typically made up of fruit trees, and they also exist at larger and income-generating scales alongside seasonal crops.

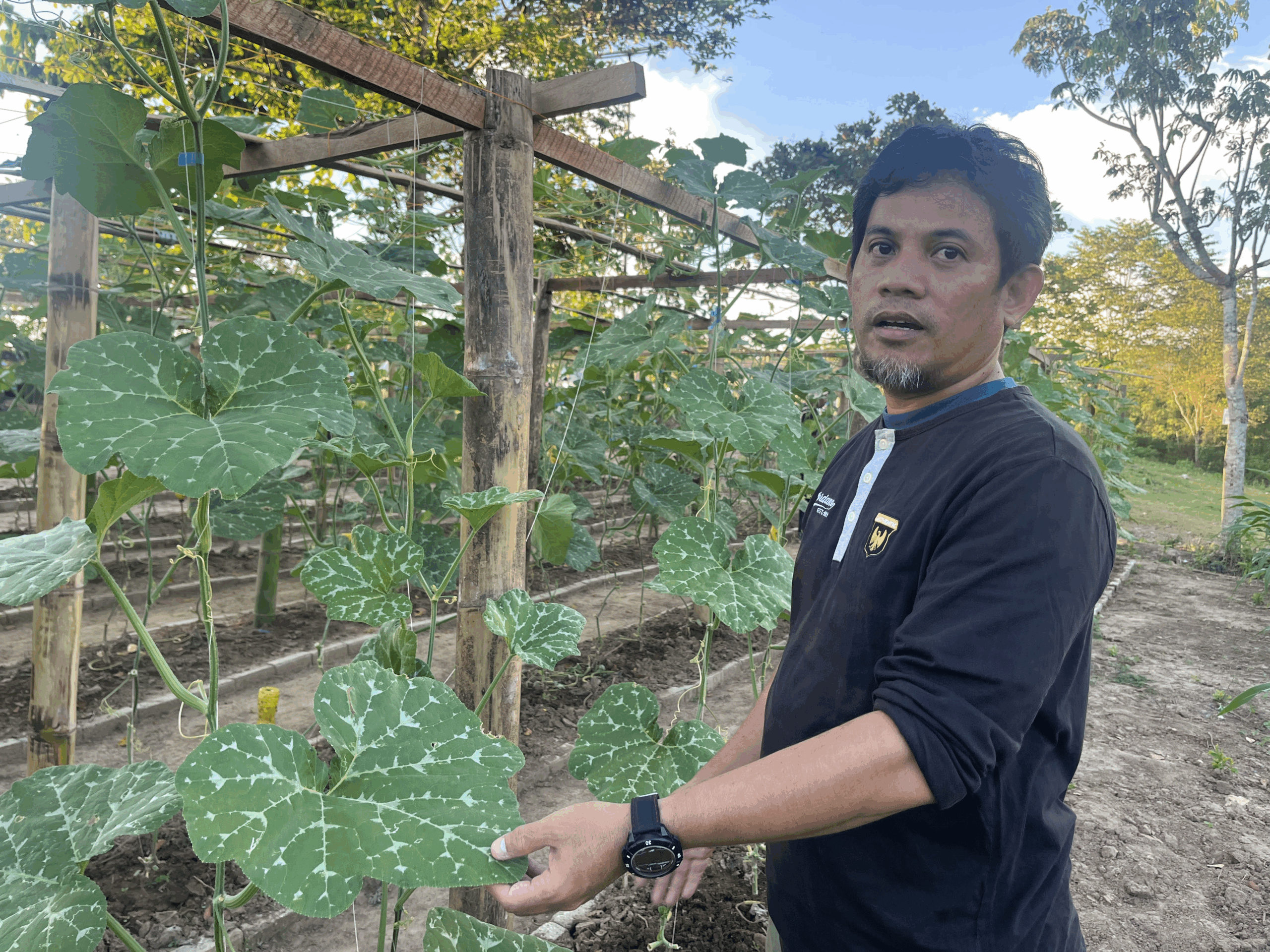

As these communities navigate changing circumstances with mixed success, innovations are also taking place. Universitas Negeri Gorontalo’s Living Lab, established under the LEAF Indonesia project, is now adapting these approaches to demonstrate the climate resilience and economic viability of integrated crops on a rural food estate.

The Lab is being developed and run with around 200 students, many of whom have personal or professional connections to monocrop farmers affected by changing priorities and conditions in Indonesian agriculture. Students are developing low-cost techniques of contour farming, soil and soil nutrient conservation, and nature-based forms of pest control, and exploring production and marketing channels for diverse crops.

Food Variety, Food Security

The candlenut, mahogany and sugar palm trees grown in Ilengi community forests support a vibrant habitat for birds, insects and microorganisms, and contribute to soil health and emission-mitigating carbon reserves. They also provide economic opportunities for the women who traditionally undertake the processing of palm sugar sap and candlenuts. Mahogany timber is another source of income helping to keep households afloat amidst changeable climate and market conditions.

In Kalimantan, Lembo gardens complement a minimal intervention approach allowing local plants to grow naturally and organic litter to be left on the land as nutrient input, underpinning a balanced agroecosystem. Here value is placed on the gains of certain compositions of the ecosystem rather than single commodities. Natural predators rule out the need for chemical forms of pest control. In fact, some gardens are used to grow natural forms of insecticide.

In West Papua, national plans to convert 250,000 hectares of land will impact a complex patchwork of communities who may differently favour the status quo. Transmigrant communities here often depend on growing hybrid rice using government-subsidised fertiliser. Meanwhile, indigenous groups use Sasi-managed forest land to grow upland rice.

From Local Practices to Scalable Solutions

Agroforestry systems, with their focus on product diversity, can simultaneously support biodiversity, climate resilience, livelihoods, and food security—even in contexts shaped by transmigrant populations and monocrop cultivation.

Expanding food estates must engage with these varied local realities. Innovative initiatives like the LEAF Indonesia-supported Living Lab demonstrate how local knowledge from one area can be adapted and scaled collaboratively to benefit another.

Learn more about Leaf Indonesia

Photo captions and credits:

Image 1: Forest farmer tapping palm sugar sap, used for making brown sugar, in Dulamayo, Gorontalo. Credit: Iswan Dunggio.

Image 2: Women farmers harvesting corn in South Dulamayo, Gorontalo. Credit: Iswan Dunggio.

Image 3-4: The LEAF Indonesia team and students at Universitas Negeri Gorontalo’s Living Lab. Credit: Jonathan Dolley.

Image 5: Universitas Negeri Gorontalo students at the university’s Living Lab. Credit: Jonathan Dolley.

Image 6: Food security, biodiversity, climate resilience and local livelihoods in a village in Papua visualised through a rich picture, one of the participatory methodologies LEAF Indonesia is using to map these interactions.