13 November 2025

post

Recognising Indigenous Stewardship of Nature in Cambodia

13 November 2025

post

Recognising Indigenous Stewardship of Nature in Cambodia

11 November 2025

post

Turning Biodiversity into Livelihoods: Lessons from West Kalimantan’s Peatlands

22 September 2025

post

Principles for Inclusive Nature Action: Driving gender-responsive, locally-led, rights-based approaches to sustainably using, protecting and restoring global biodiversity

19 September 2025

post

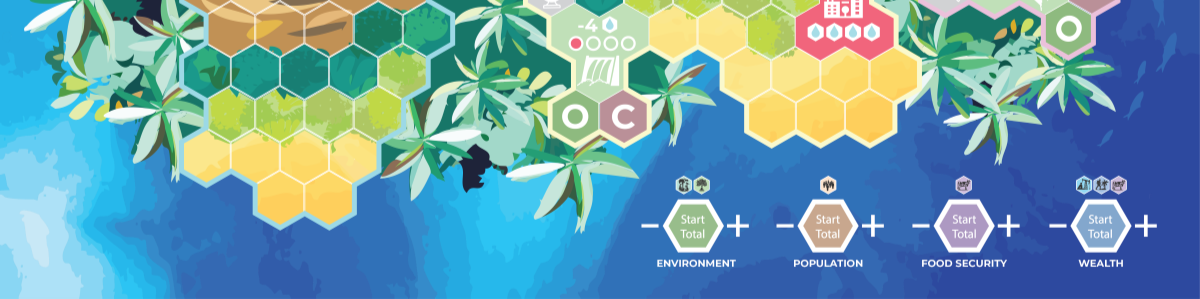

Enhancing Coastal Ecosystem Services: ENHANCES Explores Solutions through Games

15 September 2025

post

Embedding GEDSI: Strengthening Inclusive Biodiversity Action

27 August 2025

post

Saving Lake Sofia: From Rescue to Restoration in Madagascar

29 July 2025

post

Weaving Transformative Resilience and Active Hope: An Alliance in the Face of Climate Change in the Gran Tescual Indigenous Reservation

24 July 2025

post

Recognising Indigenous Knowledge in Cambodia’s Biodiversity Management

23 July 2025

project

Deploying Diversity for Resilience and Livelihoods

17 June 2025

post

People, Nature, and Resilience: Launching ILWGAWS in Ghana’s Coastal Wetlands